“I see here an excellent track record in Classical and Byzantine philology. And some research on modern Greek linguistics. Listen to me, keep up the good work on the former and ditch the latter: studying the margins will not do much to your career”. I was a young scholar trying to carve a space for himself in Academia and interviewing for an assistant professorship when a senior colleague far ahead in his career gave me this unsolicited advice. It hit hard and run through me as a bolt of realization: regardless of how useful that would turn out to be, the path I had taken in my studies was exactly the one I wanted for myself.

There have been constants in my career. I have always believed in a broad diachronic approach to the study of Greek antiquity. To specialize in a particular segment of the thousands year-old life of the Greek language, or to focus just on one author or literary genre should not prevent us from being culturally open to all phenomena that originated and still originate in the Greek-speaking communities. Including the so-called peripheral areas, whose Greek-speaking minorities have a tradition going back hundreds if not thousands of years. Such minorities have seen their language evolve in parallel with the language spoken in the geo-political area of Greece, and have produced literature, in prose and verse, orally transmitted for centuries. Now, more than ever, these works are in need of being transcribed and studied.

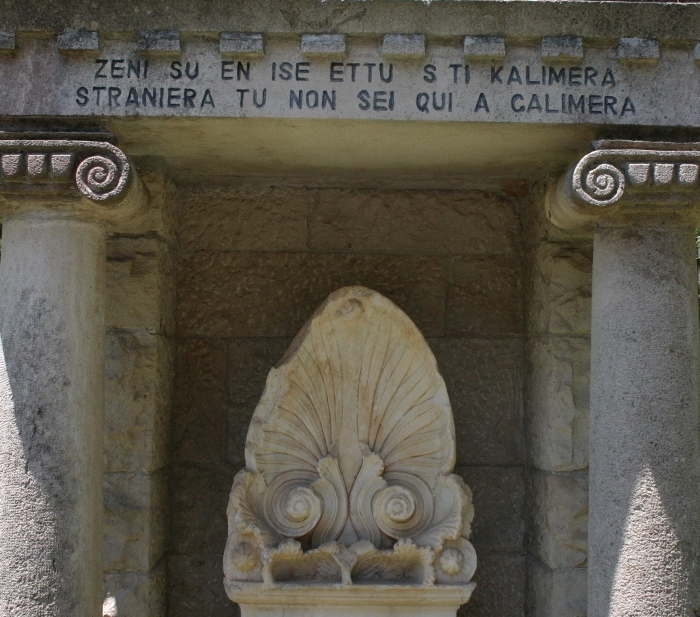

It is not even a choice for me. Like Odyseas Elytis, I can say “Greek, the language they gave me”. I was born into a family that speaks Greek, or rather ‘grico’, namely the neo-Hellenic dialect of southern Apulia in Italy. After an initial training in classical philology, I devoted myself to the study of Medieval Greek. I have always continued to speak “my Greek” at home, and the more I delved – as my studies and my age progressed – into the historical evolution of the Greek language up to the Neo-Hellenic “vernacular”, the more I discovered how much my mother-tongue is a treasure trove of words layered and textured over the centuries. One that still continues to be enriched by contributions from and contacts with other languages. This treasure, however, is not safe. It is endangered by the ever-decreasing number of speakers, which will eventually also lead to the gradual disappearance of its great literary heritage. Alas, the same goes for all the historical Hellenic-speaking minorities, from the Ukrainian Donbas, to Trebizond in Turkey, to the Himara of southern Albania.

As I said, it is a language inscribed in the memory of our communities as well as in my own personal memory. And the two not rarely intersect. I still fondly remember the notebooks I used, when, at the tender age of fifteen, I started transcribing the Greek poems recited to me by the elders of Salento. It was my first attempt at linguistic and anthropological research, made up of short notes in the margins in which I jotted down the Classical Greek equivalents – which I had heard in the classroom – to try to make sense of the history behind those poems. It is then that I began to divide the texts based on their content and tried to identify metrical forms.

Fast forward twenty-five years, I am still busy collecting and studying those sources, now armed with the principles of linguistics, philology, and literary criticism. But it is now time that a new generation of scholars try their hand at the task. The contribution of fresh eyes looking at those age-old words with renewed passion will certainly help clear the field from the prejudices that still partly weigh down this research. After all, the very notions of centre and periphery are questionable. Any linguistic and literary expression of Greekness, when looked at from a narrow and exclusive perspective can appear marginal and peripheral. However, when we broaden the spectrum of our research, each phenomenon finds its proper place in time and space and becomes key to piece together the larger picture of a complex interconnected system.

It is also time for universities to get back in touch with their territories, understand their needs, interpret their requests, and deal with their cultural expressions. The University of Salento has set itself this goal and has been working in this direction for some time now. We are now waiting for the AntCom PhDs to join us and walk the streets of Salento, ready to immerse themselves in a wonderful natural and anthropological context and recover the ancient Greek voices still inhabiting it.