Ever since I was a student, I had been fascinated by the Biblioteca Capitolare in Verona. The library stood out in the textbook on the transmission of the classics we read at the University of Copenhagen in the 1980s, Scribes and Scholars. I soon got interested in the early humanists, not least Petrarch and Boccaccio and their exciting library travels – including the Capitolare. Later as a tourist – and as a manuscript scholar – I gazed at the inconspicuous and closed doors. I knew that it was an ecclesiastical institution and had never figured out exactly what it took to get the opportunity to consult manuscripts there.

My chance came with AntCom! Thanks to our Verona colleagues, especially Paolo Scattolin, and their collaboration with the library, I was allowed in to consult four exceptional ancient and early medieval books on October 13 and 14. It was quite extraordinary to be there and my sincere thanks go to prof. Scattolin and to the library staff.

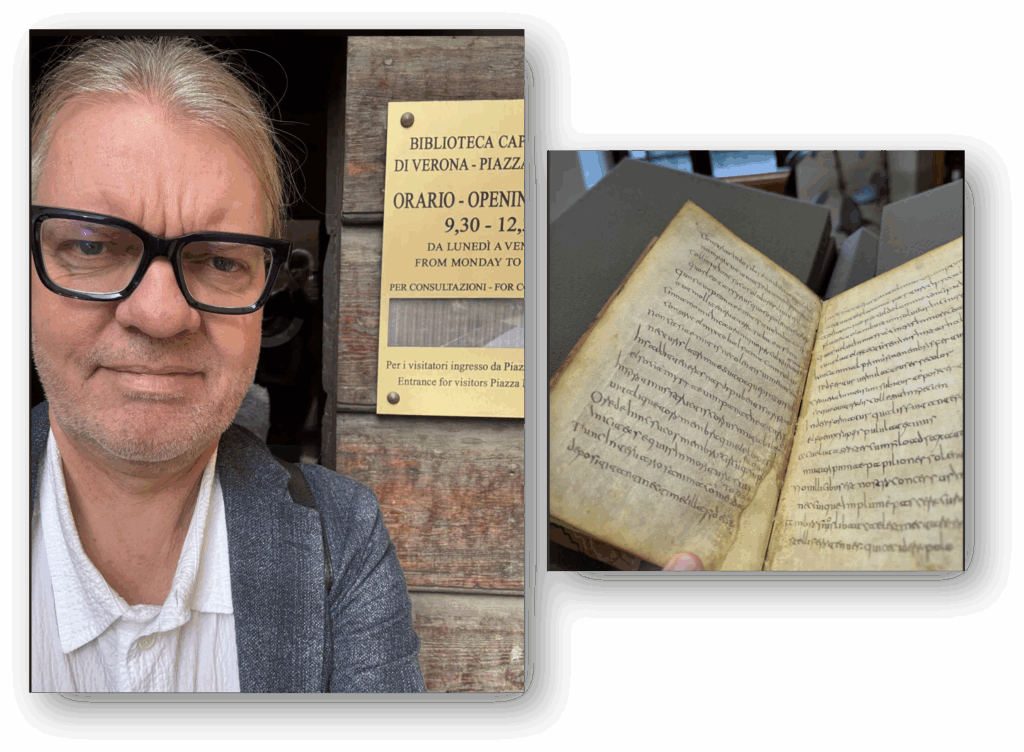

The first morning I spent in the company of a school book copied in Italy, very probably Verona, in the second half of the eighth century. We know it is a school-book both due to its physical characteristics and the texts it contains. It is small – only 20×13.5 cm, made of medium quality parchment and written in an “inexpert, individual pre-Caroline minuscule” – according to the standard catalogue of pre-800 Latin manuscripts, the Codices Latini Antiquiores (CLA).

The book is incomplete: the first extant quire is numbered “iiii” and it is also damaged and deficient at the end. But what is left shows us that it consisted of a selection of short poems by Claudianus (active around 400 as a court poet for emperor Honorius and his chief advisor, Stilico) and the socalled Disticha Catonis, a late antique school text made up of easy to learn two-liners about good behaviour and virtuous life. One of the things to be observed only with the manuscript in hand is that the two sets of texts were copied as one integrated book for school use (scholarship has had a tendency to report on the manuscript with interest in only one of the texts, or exclusively with focus on the script).

It was frankly amazing to sit with a school-book containing classical authors, copied on the brink of the Carolingian Renaissance, in Italy and most probably in Verona. If the date of the book is for instance around 760 or 770, it just predates or is contemporary with the emergent rediscovery of classical authors made by Carolingian scholars in Italian libraries. One can only wonder if the exemplar of this school book might have been quite close to Claudianus in time, perhaps a fifth century school book in cursive or rustic capitals? In any case, part of the fascination of this modest little book is that it is our first extant textual witness to Claudianus’ work – made close to where he had recited most of his celebrated court poetry c. 370 years before, namely in Milan.

One of Claudianus’s poems, in fact, describes a gentleman who lived his entire life in Verona – never left the city. And the incredible continuity we find in the collection of the Capitolare exactly bridges that gap between the age of Claudianus and the age of this Carolingian copy. This is why the library markets itself as “the oldest library in the world”.

The production and use of Latin books changed rather dramatically during the sixth century – from a rich and diverse citizen-driven book production and market to a much narrower and entirely ecclesiastical one. This is beautifully evidenced in two books I saw the next day.

One still belonged to the old way of making books, an almost square volume (22×19.5 cm), written in half uncial (headings in square capitals) on high quality light parchment containing Jerome’s De viris illustribus (with Gennadius’s update from c. 495) plus a large theological dossier on the so-called Acacian schism (484-519). It is dated to just after the mid sixth century (a list of popes ends with Vigilius’ death in 555). Strong arguments put its production also to Verona.

Next, I consulted a beautiful volume from just after the shift from ancient to medieval book types, namely a large heavy book (28×24 cm and 256 folios), in large uncial script, containing parts of the Vetus Latina translation of the Old Testament (Kings 1-4) plus a unique description of the world (Cosmographia). It was copied in the beginning of the seventh century and was in Verona at latest by the eighth century.

Finally, I was pleasantly surprised to be allowed to see some leaves of the most famous Livy palimpsest, containing parts of books 3-6 of his colossal Roman history (labelled V in the editions). It is written in the earliest type of uncial script (according to CLA), dated to the beginning of the fifth century – so contemporary with our friend Claudianus! It was overwritten in the early eighth century and has had a very chequered history, also in modern times with various experiments and repairs – which explains why it has been taken apart into separate double leaves and does not look or feel like parchment at all (some polymers were added in a more recent process, I understood from our Verona colleagues).

These stunning but confusing leaves were the last I saw this time around. It was a book historian’s dream to be there – it makes such a difference to study the books in 3D and to handle the volumes: it greatly enriches the historical imagination of how books functioned in early medieval society.