On September 9, I set off on a little journey to Copenhagen with AntCom PI, Professor Aglae Pizzone, and photographer David Binzer. Our mission was to uncover and document the decorations of the entrance hall of the University of Copenhagen’s main building on Frue Plads.

At 10 a.m., we met with communication advisor Jens Fink-Jensen outside the imposing façade. Jens, acting as our gatekeeper, ushered us into the hall—and immediately, we were surrounded by mythical tales. Towering marble figures of Apollo and Athena flanked the staircase like silent guardians, guiding visitors toward the Ceremonial Hall above. Yet it wasn’t the statues alone that drew us here. It was the brilliant 19th-century frescoes, alive with scenes from Greek mythology, which motivated our mission.

While David balanced high on a ladder, lens trained on the painted stories sprawling across the walls, Aglae and I tried to read through the paintings, piecing together the dialogue between past and present.

Why had we come all this way to capture these frescoes? Because they hold a double significance: for my dissertation, which explores how 19th-century Danes received classical art, and for a Citizen Humanities project that asks today’s viewers to reflect on what these images mean in our own time.

And indeed, the frescoes once sparked passionate debate. Back in the 1850s, reactions were far from uniform. Some, like a writer in Fædrelandet (December 17, 1853), were enchanted, praising Hansen for letting the Greek myths speak their “beautiful and sublime language” to all who entered.[1] Others bristled. Journalist Meïr Goldschmidt dismissed the frescoes in his journal Nord og Syd (1855) as “a questionable honor for the University,” accusing them of lacking coherence.[2] Meanwhile, Morten Nielsen, a farmer-soldier from Funen, left a telling note in his diary after a visit in 1856: yes, the entrance was grand and beautiful—but he lamented that it celebrated Greek gods instead of honoring the Nordic pantheon: “It is a big pretty building with a grand, exceedingly lovely entrance hall, that as far as I can recall was painted by Constantin Hansen and has only the one fault that it is the Greek gods and goddesses painted there instead of sticking to the Nordic [gods]”.[3]

These contrasting voices remind us that art has always been contested ground, a space where aesthetics, identity, and belief collide. By retracing these stories today, standing beneath Apollo’s watchful gaze and Athena’s steady presence, we are rekindling a conversation that began over 170 years ago.

The current university building was built in 1836. In 1807, during the Napoleonic wars, most of the university buildings were destroyed in the British bombardment of Copenhagen. Denmark was at the time neutral in the conflict, but the British Royal Navy bombarded the city of Copenhagen in order to force the Danes to give up their fleet to the British. As a result of the destruction of the old university buildings, it was decided that a new main building should be erected. The new building was together with Vor Frue Kirke part of the large-scale rebuilding of Copenhagen and together they frame the urban space of Frue Plads. When the new university building was finished, it was time to give it suitable decorations.

The entrance hall was one of the first spaces in the university building to be decorated, but even then it would take almost 20 years before the work was finished. At first there was a lengthy process to decide on the design of the decorations and choose the painters and sculptors for the job. In 1843, the university consistory finally decided on the proposition of painters Georg Hilker and Constantin Hansen, while sculptor Vilhelm Bissen was chosen to sculpt two larger-than-life sculptures of the Greek gods Appollo and Athena. Hilker and Hansen began working on the decorations in 1844. It would take another nine years before the wall decorations were unveiled to the public in 1853 and another two before the sculptures of Athena and Apollo, that through funds raised by the public were made in marble instead of the original plaster, were unveiled in 1855.

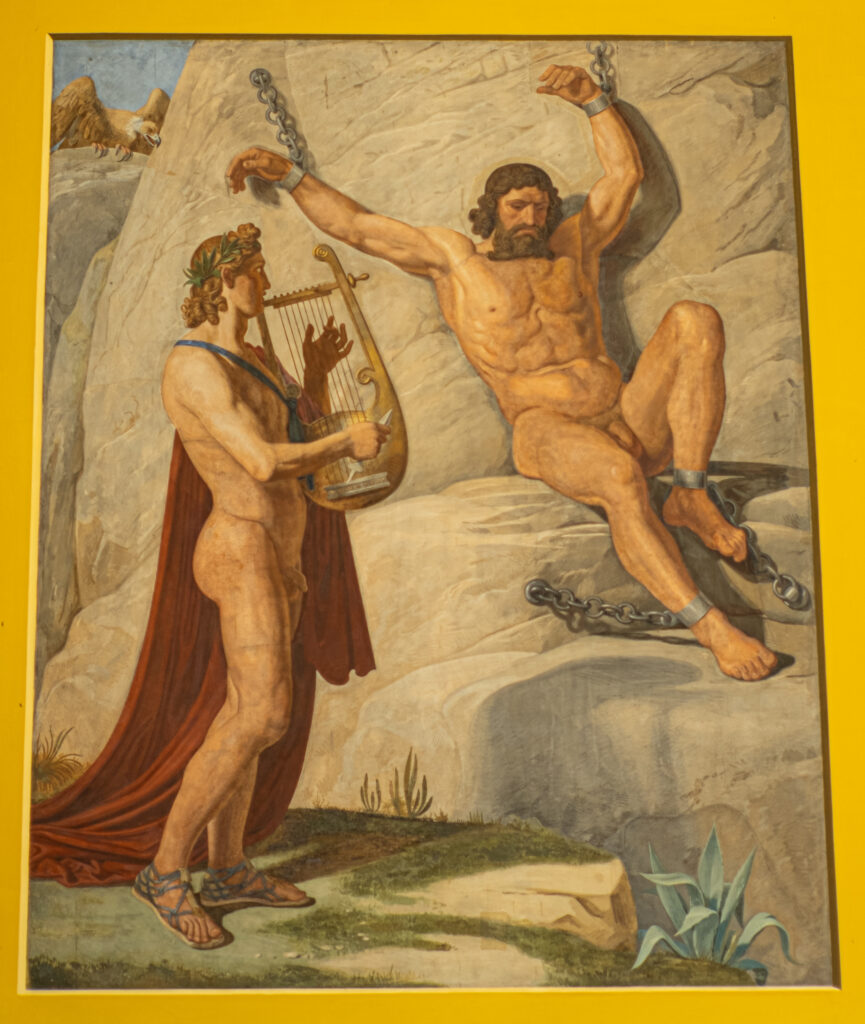

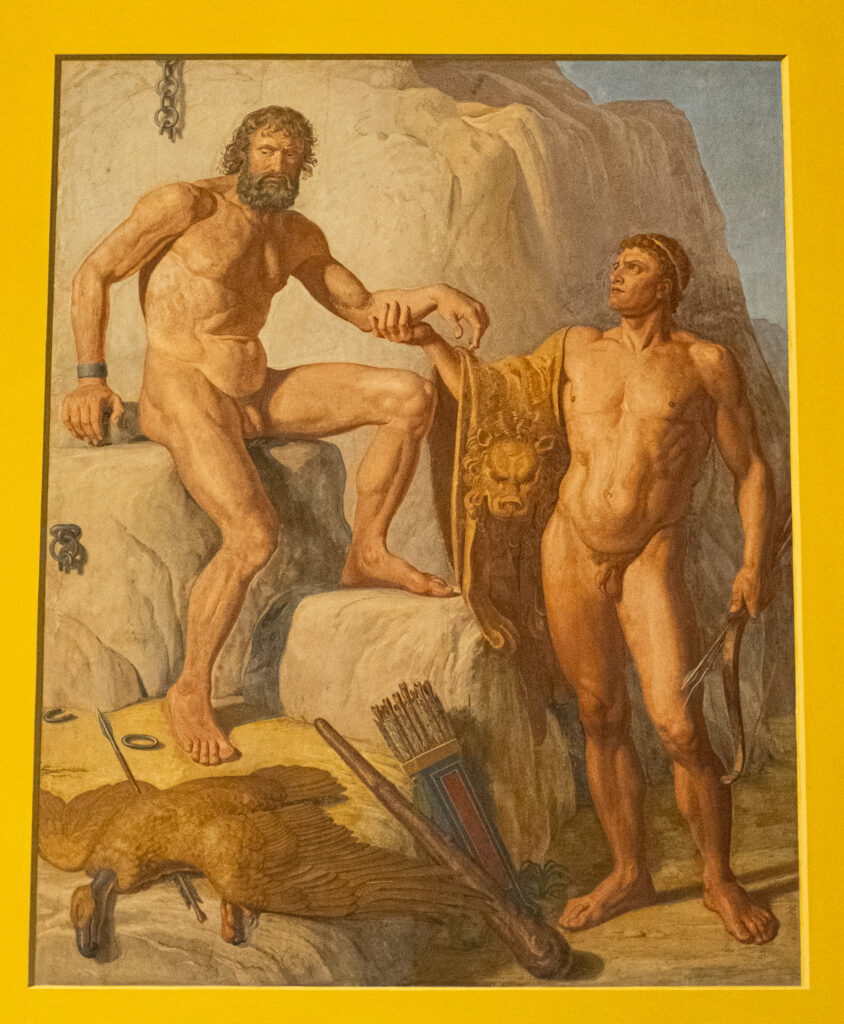

As mentioned above, the decorations depict subjects from Greek mythology. Around the room, seven huge frescoes depict myths connected to Athena and Apollo – personifications of science and culture. In the three frescoes on the central wall (the first ones you see when entering the building through the main entrance), Prometheus also features prominently. Today, I suspect Prometheus is mostly known as the titan who stole fire from the gods, gave it to mankind, and was punished for it by Zeus by being chained to a cliff and having an eagle eat his liver over and over again. Prometheus’ punishment (although Constantin Hansen painted a vulture instead of an eagle – a motif also known in antiquity) and his liberation by Heracles are depicted here. In the centremost fresco, however, Prometheus is seen together with Athena as a sculptor having made man out of clay while Athena is in the process of giving the clay figure a soul represented by a butterfly. This tradition, where Prometheus is the actual creator of the human race, originated already in antiquity. Most famously, Ovid wrote about it in his Metamorphoses 1.76-83, here in a translation by Brookes More published in 1922:

But one more perfect and more sanctified,

a being capable of lofty thought,

intelligent to rule, was wanting still

man was created! Did the Unknown God

designing then a better world make man

of seed divine? or did Prometheus

take the new soil of earth (that still contained

some godly element of Heaven’s Life)

and use it to create the race of man;

first mingling it with water of new streams;

so that his new creation, upright man,

was made in image of commanding Gods?

The two traditions – Prometheus stealing fire, thus giving man the power of invention, and Prometheus actually giving mankind its corporeal form – have survived side by side until modern times, but what is surprising in Constantin Hansen’s decorations is that he has combined them. Hansen himself acknowledged in an article from 1857 that his inspiration for Prometheus and Athena came from sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen and the bas-relief he had designed for Christiansborg Palace.[4] Hansen’s fresco of Prometheus and Athena is a close recreation of Thorvaldsen’s motif in painting, which can be seen here: https://kataloget.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk/A319.

The composition is quite unusual and does not seem to follow any pattern found in antiquity. Prometheus creating man together with Athena in the centre, flanked by depictions of Prometheus being punished makes it seem like the artist depicted the action from one myth and combined it with the consequence of the other. Why would Zeus punish Prometheus for creating mankind together with Athena? One who was confused by this depiction was the aforementioned Meïr Goldschmidt, who made it a central topic in his critical article about the decorations from 1855.

Today, the entrance hall is off limits to the public, but this was not the case when the decorations were first unveiled in the 1850’s. In fact, it was an outspoken goal from the university officials to let the general public have access to the entrance hall. The idea was that the Danish people would improve themselves and become spiritually stronger through contact with great culture from the past.

Through my Citizen Humanities project, I hope to give more people the chance to discover these remarkable decorations and explore the cultural heritage they represent. The project website will launch soon – there you will be able to view the paintings, learn about their history, and most importantly, share your own thoughts and feelings about what they evoke.

[1] U., “Universitetsbygningens Forhal.”

[2] Goldschmidt, Nord og Syd., 7:126.

[3] Vesterdal, “Beretning Om En Rundtur i København i Midten Af Det Nittende Århundrede,” 69.

[4] Hansen, “Freskomalerierne i Universitetets Forhal.”